In Estonia, Europe’s last road through Russia has closed for good

LUTEPÄÄ, Estonia — Across the snowy and muddy forests of eastern Estonia, NATO and Russia are locked in a staring match. It’s here, the frontier between a country with a population smaller than Vienna’s and the largest nuclear power in the world, that many analysts fear Russian President Vladimir Putin may one day be inclined to conduct a limited invasion into NATO.

The mood at the border here is tense and silent. Stretching inland from the tall barbed-wire fence is a “border regime area” patrolled by special police units and dotted with guard towers. There are just a few villages in this zone – many of them Russian-speaking – connected by deserted but immaculately maintained roads.

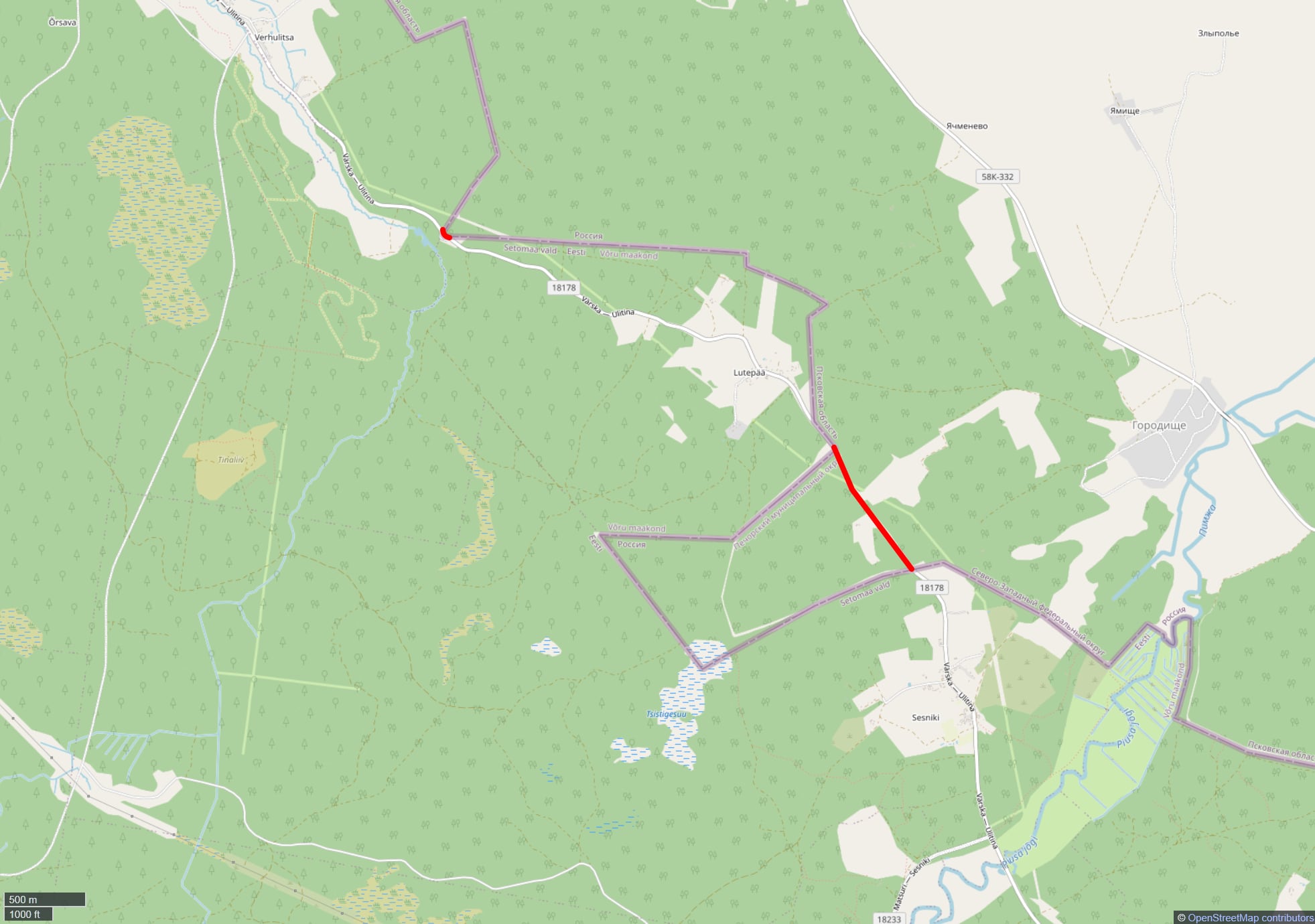

Until this fall, this border was home to an oddity that served as a reminder that, despite the politics, the people here have long been connected. Estonian Road 178, built in Soviet times, cuts through Russian territory in two separate spots, connecting several towns to the regional center of Värska. A low-key agreement between the local border guards on either side of the fence meant that residents could use the road without checks, provided they stayed in their vehicles and would not stop in the approximately one kilometer of Russian territory that they traversed.

This arrangement, never codified in official government policy on either side, came to an abrupt end on Oct. 10.

“We saw a bigger group of soldiers. Some of them – most of them – had equipment like regular soldiers, not border guard uniforms and equipment,” said Renet Merdikes, the Border Police captain in charge of this stretch of the border known as the Saatse Kordon.

Merdikes has worked all along the frontier for the past thirteen years.

“We haven’t before seen this kind of unit around,” he added.

Merdikes counted eleven Russian men in uniforms, who had come from different directions and loitered for a while in the Saatse Boot, the piece of Russian territory that juts into Estonia and through which the road cuts. They were even on the strip of tarmac itself, he said, all the while Estonian vehicles were still using it to get from Sesniki to Lutepää, two tiny villages on the southern and northern end, respectively, of the Russian pocket.

Estonian authorities quickly closed the road. It hasn’t reopened since.

“We didn’t want to wait for the first serious incident,” said Merdikes. “We can’t do anything on the Russian territory, we can’t protect our citizens.”

Strained ties

The soldiers ultimately left not long after they arrived, having walked around the area for a while and seemingly doing nothing else. Merdikes says that the Estonians picked up a hotline to their Russian counterparts, set up to defuse potential “emergency incidents,” asking for an explanation. They were told that there was nothing out of the ordinary and it was “usual activities.”

Initially, the road was blocked with a street sign, then concrete barriers and a temporary fence were set up. This week, a permanent fence has been constructed, sealing off the two road segments for good. Work has also started on replacement routes, with the longer of the two stretches set to be done by late next year, an expedited schedule pushed by the Estonian government for a project that was already underway to rectify the peculiar cross-border arrangement.

Until about 35 years ago, this line separating Russia from Estonia, which follows a river, the middle of a lake and then cuts through a series of forests, marshlands and Road 178, mattered relatively little. Since being invaded by the Soviet Union in 1940, and for five decades thereafter, the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic was just one of 15 constituent republics of the world’s preeminent communist state. The frontier between Estonia and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic – which everyone understood was the dominant power in the “union” – was just an internal border of the same country.

Personal ties across the border remained close even after the dissolution of the Union, and pragmatic arrangements like the one in the Saatse Boot were par for the course. Until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, even the Estonian border guards themselves would make use of the road leading through Russia.

Now, they have to take a detour to go around, out of an abundance of caution, the border guard captain said.

Even before the Soviet Union, under the Tsarist Russian Empire, Estonia had been under some form of Russian control for centuries. Legacies of the countries’ complicated but nonetheless shared past are plentiful – a large Russian Orthodox church, part of the Kremlin-aligned Moscow patriarchate, stands opposite the Estonian parliament in the capital Tallinn; census data shows that two in every three Estonians live in Soviet-era apartment blocks; and ethnic Russians make up more than a fifth of the population.

Still, Estonia’s national identity is distinct and specifically European. Its heritage is linked to the Hanseatic League and the traders of the Baltic Sea, and its language carries strong traces of both Finnish and German. Museums in Tallinn, are quick to point out these historic connections and relativize ties to Russia, the Soviet period being described as a phase of Russian occupation. Practically no Soviet symbols or iconography remain even in remote backwaters, with round hammer-and-sickle plaques removed from buildings, leaving conspicuous circles, and statues of Lenin scrapped.

The divided city

But ties across the border don’t disappear overnight. In Narva, a city in northeastern Estonia that is also its largest border town, there is a constant flow of people walking across the border to and from the twin city of Ivangorod, on the eastern – Russian – bank of the river, even now in late 2025. The crossing has been closed to vehicle traffic since 2022, ostensibly for construction works, although none were visible in mid-November three years later. Instead, the bridge has been fortified with tank barriers, electronic gates capable of closing within seconds, and a generous helping of barbed wire on all sides.

A little farther south, a seldom-used railroad bridge forms another physical connection between the two countries, spanning a gorge forged by the Narva River.

Since Jan. 1, 2023,, a year into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Estonia has suspended all cross-border rail traffic from and to the east.

A bored-looking Russian border guard, Kalashnikov rifle slung over his shoulder and dressed in a thick camouflage coat, observed this Defense News reporter through his binoculars as he snapped pictures of Russian fishermen braving the cold and reeling in a meager haul on his side of the river. The soldier was the only sign of activity on the once-busy railroad bridge.

Just south of the city, next to the abandoned Soviet textile mill that used to employ 13,000 people, a dam spans the river. No crossing of the border is intended here, as is made clear by the razor wire and two opposing guard towers, myriad cameras and warning signs with a big red exclamation mark on a bright yellow background.

There were several other people on this dam on a blustery late November day, just short of the fence, pacing up and down and speaking into their phones in Russian. The manmade peninsula, it seems, juts far enough into Russia’s cell network to make domestic phone calls with a Russian number. Geopolitics has hardened this previously porous border, but the connections across it are similarly entrenched.

But they are becoming harder to maintain. Many crossing points have been indefinitely closed and others are open only to pedestrians or specific types of travelers, and sanctions have ground cross-border economic activity to an effective halt.

The frontier itself is being fortified, too.

“Border building is ongoing right now,” said Merdikes. A modern fence is already installed along most of the land border. In the Saatse area, the current project is to create a gapless string of cameras to observe every meter of the fence. “Our goal is that we have eyes throughout the border so we know where to react,” said Merdikes. “We are the first eyes on the border in case something happens.”

Fortress Baltics

Beyond the immediate fence, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have teamed up to construct what they dub the Baltic Defense Line. The project was announced in January 2024, and construction is now ongoing in all three Baltic Republics.

Primarily meant to deter and, if necessary, slow a Russian invasion, it will consist of a series of anti-tank obstacles, dragon’s teeth, barbed wire coils, bunkers and areas designated for laying landmines should the situation necessitate. Estonia alone plans to build 600 bunkers along its frontier with Russia, and the other Baltic states are expected to follow suit. The plans are being coordinated multilaterally between the countries and within the framework of NATO, according to the Estonian government.

“The war in Ukraine has shown that taking back already conquered territories is extremely difficult and comes at great cost of human lives, time and material resources,” said the Estonian National Defence Investment Center ECDI in a report outlining the large peacetime construction project. “In addition to equipment, ammunition and manpower, we need physical installations to defend our countries efficiently.”

Estonia expects to spend around €60 million ($70 million) on the project. It is meant to be completed by the end of 2027, according to the head of infrastructure at the Center for Defense Investments, Kadi-Kai Kollo. This represents a delay of about a year due to unexpected complications in developing the modular bunkers that are to serve as the main backstop of the fortifications.

“We have seen different estimates on how quickly Russia can rebuild its military, we need to use this time wisely – the time to make all the necessary preparations is now,” the ECDI report said.

The last remaining Soviets

On the Soviet-built House of Culture in Sillamäe, a grand Stalinist building, hangs a conspicuous sign featuring a blue triangle on an orange base. Scattered around Estonian towns, this sign marks that the building has a publicly accessible bomb shelter. The symbols started appearing in June 2022 as a direct consequence of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the fears it caused in Estonia. Within six months, shelter spots for more than 60,000 residents were marked accordingly. In the case of war, they would seek refuge in World War-era citadels, parking lots, and under schools and hospitals.

Sillamäe is emblematic of the difficult relationship with the big neighbor to the east. The town on the northern coast of Estonia was constructed from scratch under strict secrecy by the Soviet Union. It housed one of the country’s main uranium enrichment plants, creating the fuel for 70,000 Soviet atomic bombs as well as the civilian nuclear power plants that dotted the empire’s territory.

In Soviet times, it was a closed city – not marked on any official maps and requiring a special permit to enter.

“Back then, the stores were always well stocked, and you could get whatever you wanted,” recalls Larisa, a resident who moved here in 1985, just before Soviet premier Gorbachev’s policy of radical reform changed everything. Today, the town is largely forgotten, and the grand, palatial architecture of the workers’ apartment complexes with a splendid view of the ocean is coming apart.

It’s hard to say whether life was better in the Soviet Union or now in the European Union, Larisa said. “People adapt.”

Like most people in this part of the country – Sillamäe is just half an hour’s drive from the border – Larisa speaks Russian at home, even though she is originally from Ukraine. At the time she moved here due to her husband’s work as a driver, it was all one country.

“My motherland no longer exists,” she said while going for a Sunday stroll along the Baltic promenade, her favorite place in town. Her passports are Estonian and Ukrainian. To her, the border, located just 25 kilometers to the east, is a distant thought.

“I haven’t crossed it in many years; I have no reason to,” she says. “I don’t even know whether it is still open.”

Fears of invasion

It’s here and especially in nearby Narva, right on the border, that some analysts worry Putin might try to test the West’s resolve with a limited incursion, perhaps modeled on how he annexed Crimea in 2014. The area is ethnically primarily Russian, its population is Russian-speaking.

Bruno Kahl, the head of Germany’s Federal Intelligence Service (BND), has said that Putin may initiate such a scenario to test NATO’s resolve on its collective defense provision in the form of Article 5, sparking a “grey-zone conflict” that doesn’t quite meet the bar for other alliance members to feel comfortable engaging in war with Russia.

Others, especially Estonians, have pushed back on the idea, saying such a scenario is improbable given the risks associated and the precautions that the country has taken.

Estonia will defend itself and is counting on its allies to come to its aid, is the government’s message.

“Would a U.S. president risk dying for Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius?” spy chief Kahl asked in an interview with Germany-based Table Media June. “We are quite certain – and we have intelligence to back this up – that Ukraine is only the first step. The NATO commitment to collective defense is going to be challenged.”

Whether it’s here or elsewhere along NATO’s extensive frontier with Russia – or if it never happens at all – the border in Estonia will remain tense for the foreseeable future. New fences will appear, bunkers will be buried, and cross-border connections will be strained.

But fundamentally, none of this is new. Russia’s presence just to the east has been a constant for many years. “Some things don’t happen overnight,” said Merdikes, the border police chief from Saatse.

“For us, we patrol the border. At the border, it’s quite calm – but still, we have to be ready and look for any changes to the threat level.”

Linus Höller is Defense News’ Europe correspondent and OSINT investigator. He reports on the arms deals, sanctions, and geopolitics shaping Europe and the world. He holds a master’s degrees in WMD nonproliferation, terrorism studies, and international relations, and works in four languages: English, German, Russian, and Spanish.