How the European Defence Agency can unleash Europe’s startups

The latest European Defence Agency (EDA) annual report paints a hopeful picture. Europe is finally showing signs of strategic geopolitical maturity: prioritizing defense cooperation, investing in emerging tech, and consolidating ways of operating that have historically been fragmented across its member states.

There’s reason for optimism. But still, something is holding Europe back with regard to its defense: its failure to harness its startups.

Although the EDA is the coordinating hub of the EU’s defense efforts – aligning national priorities, facilitating joint procurement, and translating political ambition into operational reality – it remains difficult for small, fast, high-tech firms to gain access.

That matters because in today’s defense landscape, speed counts as much as, if not more than, scale. Innovation is taking place not in big, state-run research centers but in small labs, university spinoffs, and dual-use companies whose teams think in weeks and months instead of years.

RELATED

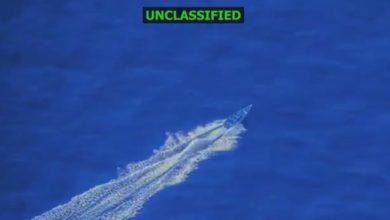

In Ukraine, companies like these are the ones making a difference. Cheap drones, made by university-age tech entrepreneurs, are taking out massive, expensive tanks.

Even companies that aren’t new to defense – companies whose products are already deployed in NATO operations – struggle. Even with a proven track record, a company is liable to find the EDA system opaque and that navigating it is painfully slow. Access to the right forums requires insider knowledge, open calls are rare, and the paths to partnership are littered with red tape.

China, and probably Russia, don’t have this problem. They integrate startups quickly into their military-industrial bases, and marshal the vast resources of the state to scale promising startups and keep bureaucracy to a minimum.

The United States, too, doesn’t have this issue. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) takes calculated gambles on emerging tech, makes open calls and supports a culture of big thinking. One in four American defense contracts now goes to a small business, and DARPA investment is behind the development of the internet and autonomous vehicles.

On the surface, it looks like Europe is trying to follow suit. Through the European Defence Fund, the EDA supports SME-led initiatives. It is strengthening ties with Ukraine, Norway, and the United States. Its interest in AI, autonomous systems, and materials science shows it recognizes where the future lies. And in 2023, the EDA managed over 100 research and technology projects worth €681 million ($774 million).

But in strategic terms, that investment is a drop in the ocean, and these moves have yet to become more than promising gestures. If the EU is serious about its autonomy and resilience, it has to increase both the scale and speed of defense innovation, which means opening the gates to the startup world and inviting the companies in.

Let’s be practical. What we need to see are routine open calls that are well-publicized and transparent. We also need entry into expert groups, such as CapTechs, to be streamlined. We need to fast-track startups with relevant, dual-use tech so that whatever they’re building can go from the lab to the field without fuss and paperwork, and enter into rapid feedback loops that mean constant iteration.

And we need more proactive outreach. Startups must have access to the strategic plans of the military in order to develop in the right way, and in the right direction and to propose solutions to military leaders. If it’s true that Europe must be able to defend itself within 18 months – and this is what some leading voices are saying – then it should be hammering on the door of every promising startup on the continent, not waiting to be approached.

Europe must also consider abandoning university civil clauses that block them from engaging with defense, and make dual-use a prerequisite for research grants. This is easy to do, and would make a world of difference. Europe is home to some of the most brilliant engineers and thinkers in the world. We already educate the talent; why do we then sideline it?

Don’t get me wrong: the EDA has accomplished much already. It has brought coherence to a scattered defense landscape. That’s no small feat. But it does have to go further. We need cultural change. It simply has to be made easier for people outside the traditional ecosystem to contribute to Europe’s defenses. That means acting more quickly, communicating more plainly, and building mechanisms that reflect how innovation actually works today.

It’s in everyone’s interest to do this. Because the future of European security will not be built by bureaucracy. It will be built by those willing to take risks, move fast, and reimagine what defense can be.

And they’re already here. We just need to let them in.

Robert Brüll is CEO at Aachen, Germany-based FibreCoat.