How did a scrap of George Washington’s tent end up at Goodwill?

In 1778, while serving as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, George Washington accepted the delivery of a new campaign tent that would accompany him through all the fire and chaos of the American Revolutionary War.

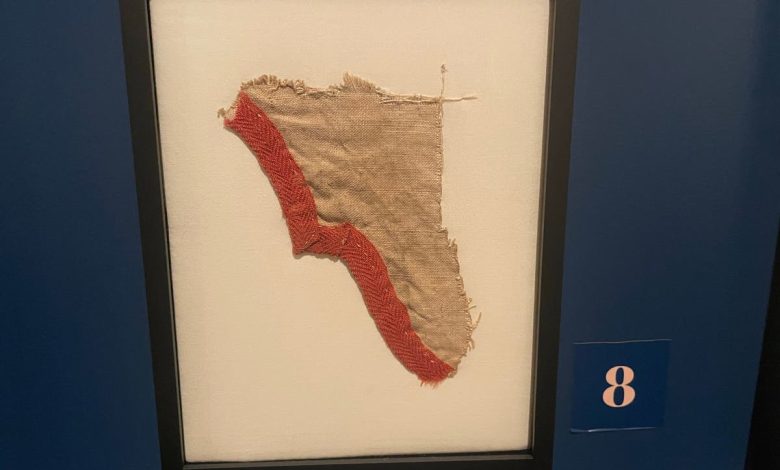

Nearly 250 years later, a fragment of that tent turned up on Goodwill’s online thrift store – for the barely believable price of $1,700.

History buff Richard ‘Dana’ Moore, 70, paid the tiny sum for the scrap of fabric in an online auction in 2022. Suspicious of its provenance, he initially kept the purchase hidden from his wife.

“I was like, ‘this can’t be’,” Moore told CNN. “There are a lot of fakes out there. There’s always something that’s not real, that looks to be real.”

In fact the fragment was authentic, and today it is on display at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, along with the rest of the tent.

“The discovery of this fragment adds to our understanding of the growth of Washington’s tents as symbols of the fragile American experiment in liberty, equality, and self-government,” Museum curator Matthew Skic told The Independent. “The tents, and each fragment of them, serve as tangible links to the founding of the United States. They help us realize the hard work and perseverance that was required to create this nation and is still required to safeguard its future.”

So how exactly did this relic of American history end up in Goodwill?

‘The Washington treasures’ and the Civil War

The story of Washington’s tents begins in 1778, when his previous tents apparently wore out and needed replacing. He had three in total: a baggage tent, a large dining marquee and his own personal bedroom and office tent, which is where this fragment came from.

Museum chief executive Scott Stephenson told The Philadelphia Inquirer that Washington would regularly set these tents up on the highest hill available, so that they were easily visible to his soldiers.

After Washington’s death in 1799, the tents became a family heirloom, together with other pieces of memorabilia such as fine china and the old general’s actual deathbed.

Washington and his wife Martha had no biological children of their own, but Martha had four from a previous marriage. Hence, the artifacts were passed down into the hands of her grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, a prominent Virginia slaveholder and plantation owner who had served in the War of 1812.

In those days, the USA was still exceptionally young, and its power appeared precarious. Custis considered himself a custodian of Washington’s memory, often pitching the tents on the grounds of his manor to host events. In the 1820s, he began cutting pieces off as souvenirs.

Custis’s daughter, Mary, married Robert E Lee, the future Commander-in-Chief of the Confederate Army. She was as evangelical about Washington’s memory as her father, and turned the couple’s grand mansion in Arlington, Virginia, into a private museum for the so-called “Washington Treasures.”

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the Union Army occupied the couple’s house – which was strategically situated atop a hill south of the Potomac, within artillery range of Abraham Lincoln’s White House.

Some of the soldiers began stealing artifacts, but were confronted by Mary Custis Lee’s personal maid Selina Gray, who alerted their commander and secured the treasures’ safety.

A note from 1907

Following the war, Custis Lee and her children engaged in a decades-long campaign to demand the government give back the treasures, which they ultimately won in 1901.

That is how the tent ended up on display at the Jamestown Exposition in Virginia in 1907. Mary Custis Lee’s daughter, also called Mary, had loaned it out for the event (two years later, she would sell it to a collector to raise money for Confederate war widows).

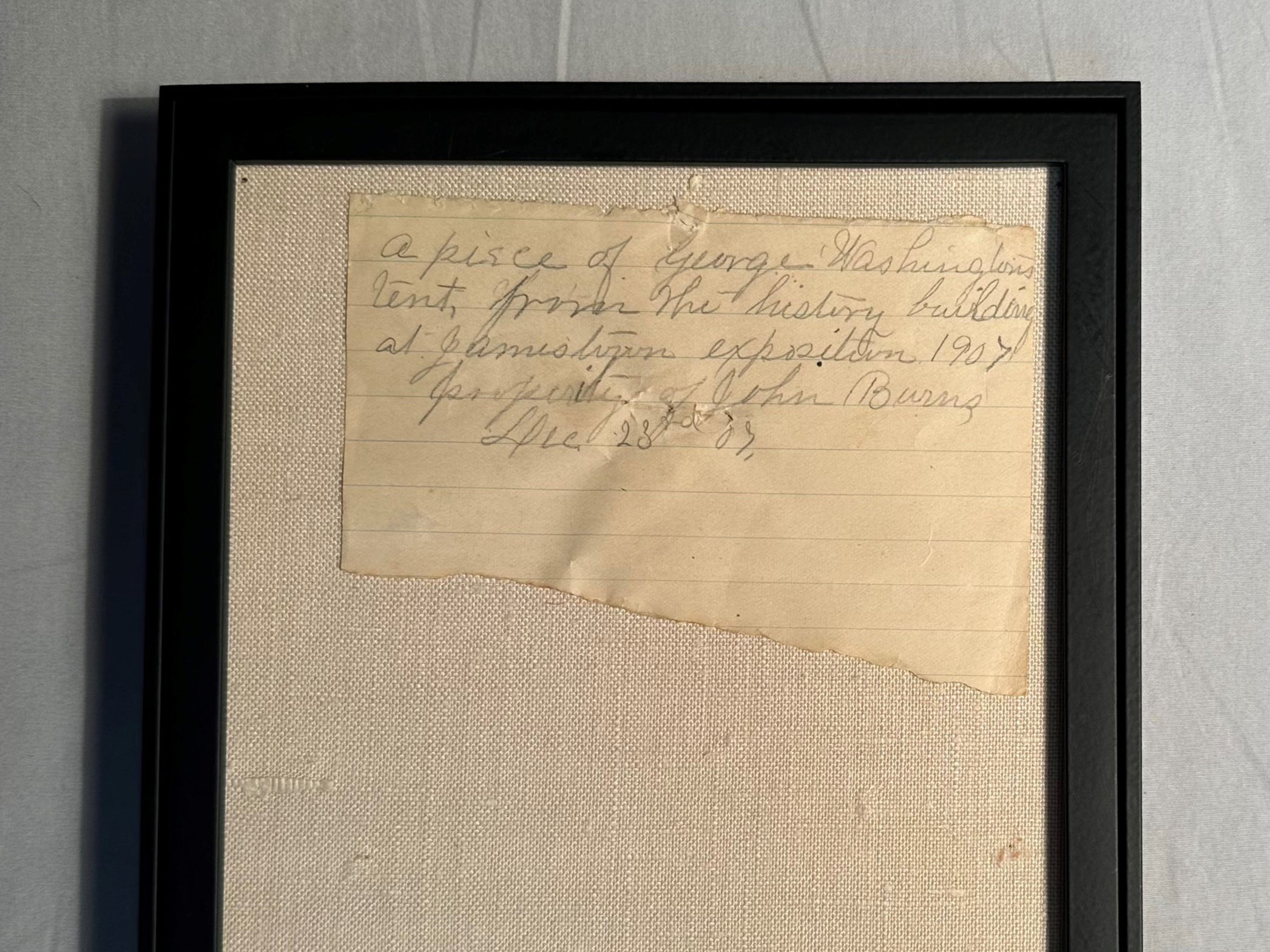

This appears to be where the fragment bought by Moore was cut. A note included with the fragment reads claims that it was taken “from the history building at Jamestown Exposition 1907”, adding that it is “property of John Burns Dec 23rd 07.”

After that, the fragment’s path is unclear. Historians don’t know what Burns did with it, nor how it ended up being given to Goodwill.

For now, it will be on display at the Museum of the American Revolution as part of an exhibit called ‘Witness to Revolution: The Unlikely Travels of Washington’s Tent’ until January 5.

After that, it will return to Moore, who says he and his wife were overjoyed to see the relic on display earlier this month.

“I never got chills like that in my entire life,” Moore told CNN. “We were both over the moon. We still can’t believe it.”