From temple donations to family visits, how Kamala Harris is still the pride of her Indian ancestral village

Between the coconut trees, bungalows and rice paddies of this remote village in southern India there is a bizarre sight: a collection of giant blue posters adorned with the face of US vice president Kamala Harris, each wishing her – in the local Tamil language – luck for November’s presidential election.

It is more than a century since Harris’s grandfather was born here in Thulasendrapuram, a tiny hamlet some 300km away from the state capital Chennai. Yet remarkably the Democrat and her family still maintain good ties to their ancestral home, a fact that has won her a village full of adoring fans a world away from Washington DC.

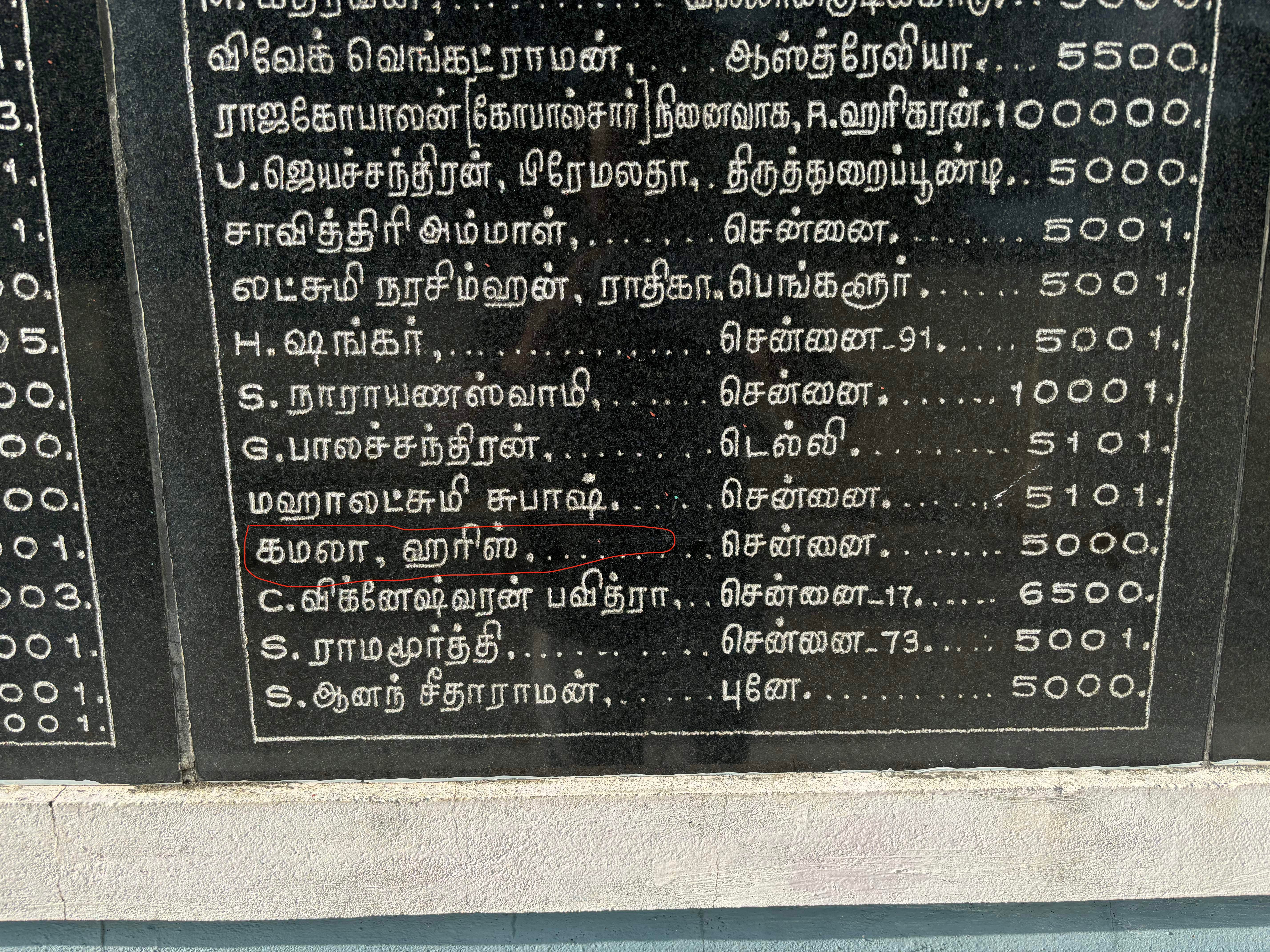

Outside the village’s 300-year-old temple dedicated to the Hindu deity Sastha there is a black stone tablet, proclaiming the names of major donors. There, written alongside an amount of Rs 5000 (£46.50), is Kamala Harris – a record of an offering made in her name in 2014, at at time when she was still serving as California’s attorney general.

The Sri Dharma Sastha Temple is abuzz at 6.30am with shops opening ahead of morning prayers. Siva Kumar, the priest in charge of the morning schedule, recalls a relative making the donation to the temple’s consecration on Harris’s behalf.

“Even after her family has moved from the village, they still sponsor prayers at the temple, not giving up on their roots. That is a source of pride for us,” says N Maheshwari, who runs a grocery shop close to the temple.

Harris’s grandfather PV Gopalan was born in Thulasendrapuram in the early 1900s and moved away from the village, first to Chennai and later to Delhi, to become a civil servant in British-ruled India. His success paved the way for Harris’s mother, Shyamala Gopalan, to move to the US when she was 19 to study biomedical science at UC Berkeley. It was there that she met her future husband Donald Harris, an immigrant from Jamaica.

Almost everyone in the village seems to be aware of Harris’s family history, even though the home where that story began no longer stands. People here appreciate that the family remembers where they came from, and that members of Harris’s family living in India still stop by regularly.

“Her uncle Balachandran from Delhi and aunt Sarala from Chennai visit the local temple about once a year. The family is still connected to the village,” Ramalingam, who lives near the temple, tells The Independent.

Further down the village’s main road, a couple of hundred metres from the temple, is a neighbourhood of Brahmins – caste segregation remains a phenomenon in many rural parts of India – where residents say Harris’s grandparents most likely lived.

The homes here have large thinnais or raised platforms on their verandahs, characteristic of homes for better-off families in villages in the area, along with other features like concrete floors and a large tank to store water in one corner of the house.

Round the corner lives retired banker N Krishnamurthy, who has become something of a local authority on all matters relating to Harris and her ancestors.

“Some 80 years back one Gopal Iyer (Mr Gopalan) was living here with his wife Rajam. They were staying here at a house in this corner at the end of the agraharam. Now the house is not there. The place is nothing but a barren land now,” he says.

While talking to The Independent he repeatedly fields phone calls from people enquiring about Harris’s latest election prospects now that Biden has stepped down from the race, leaving her the presumptive Democratic candidate.

“Ms Harris was not so well known in the village until it was announced she was the vice presidential candidate [in August 2020]. This was when we started gathering information,” says Krishnamurthy, who has lived in the village for the last 15 years.

Harris is said to have visited Thulasendrapuram herself when she was five years old, and in interviews has recalled memories of walking with her grandfather on the beach in Chennai. She hasn’t been back to Tamil Nadu, or indeed visited India as a whole, since becoming vice president.

Nonetheless, residents here say there will be big celebrations if she can go one step further and enters the White House. Maheshwari, the shopkeeper, points to a calendar with photos of president Biden and Harris that occupies pride of place on the counter.

“Even people who migrate from the village to some place further north within India forget their ancestral deities,” she says, contrasting this to Harris and her family.

“We have been following her journey since she was nominated vice president in 2020. Back then we conducted special prayers at the temple when she won and distributed sweets to celebrate her victory. We will do it again if she becomes president this time.”

Some villagers suggest a win for Harris could strengthen ties between the US and India, although they are realistic about whether any benefits would extend to this tiny village 8,000 miles away from Washington DC.

“There was a lot of news coverage about our village when she became vice president, and afterwards officials, including some from the US consulate, came to inspect schools and water bodies here. Nothing happened after that,” a resident says as she prepares fodder for her cows.

“Even now we understand there’s not much in her power to help the village, but we still hope she wins,” she says.

Assuming she is named the Democratic nominee at the party’s convention next month, Harris will face Donald Trump in November’s election, and there are plenty of fans in India for the Republican who, during his time in office, found a kindred spirit in prime minister Narendra Modi.

There are no Trump supporters to be found in Thulasendrapuram, however, with many residents saying they are only interested in following the US elections because Harris is involved.

One villager, Maniyan S, puts it like this: “Trump is an American. But Harris is a woman with Indian roots, and her ancestry is from our land. It would be a source of great pride if a woman from our land wins the American election.”