Did the Alcatraz escapees live out their days in freedom in Brazil? Their nephew’s new book says yes

The letters came to a Georgia PO box, 17 of them in all, missives written behind bars by an infamous Irish mob boss to the nephew of history’s most legendary jailbreakers.

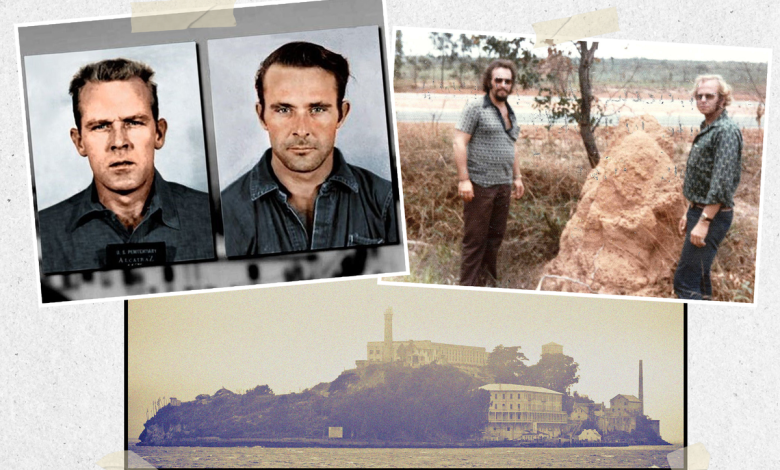

James “Whitey” Bulger had sought out correspondence with the family of John and Clarence Anglin, two brothers he’d met in prison who went on to escape Alcatraz with a fellow felon in 1962. The trio were never found but presumed dead by the FBI, which closed the file in 1979 – the same year Clint Eastwood’s Escape from Alcatraz added further celeb status to the already famous tale of breaking for freedom from The Rock.

Bulger reached out through an emissary to the Anglins during the 50th anniversary events being held on the California island, now a national park and no longer an operating correctional facility; among the relatives attending in 2012 was Ken Widner, son of Marie, one of the Anglins’ 12 siblings.

He and the numerous other Anglin cousins had grown up among hushed whispers, winks and quickly-changed subjects; their relation to the notorious and colourful Alcatraz escapees had always been the only reality they’d known. Widner had been a baby on his mother’s knee as she watched news reports of her brothers’ jailbreak but now, decades later, his curiosity was growing – along with a desire to more three-dimensionally set the record straight about his uncles’ lives.

That included how they grew up, who they were as men, how they fooled authorities and, most importantly, how the family says they secretly succeeded in their escape– eventually making their way to South America, where they carved out lives and families in Brazil.

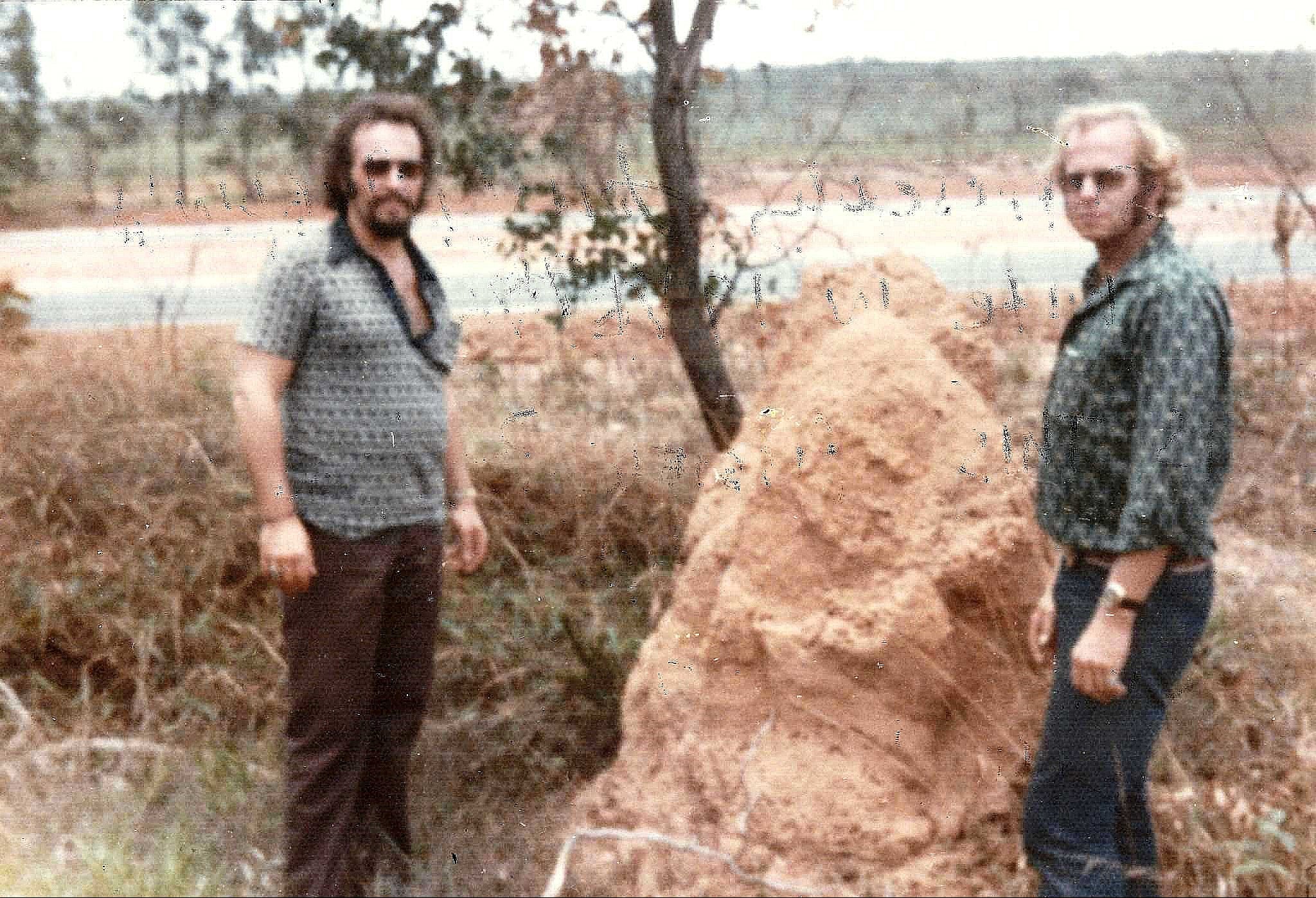

Widner and his relatives have the picture they believe can prove it – as they work to hunt down long-lost relatives in the bowels of the world’s seventh most populous country.

And Boston mobster Whitey Bulger – the man Widner calls “James” who spent 16 years as a fugitive before his 2011 recapture saw him charged with 19 murders – would prove invaluable in doing so.

“He thought very highly of John and Clarence,” Widner says of Bulger, who first met the pair in prison in Atlanta in 1958 and ended up serving time with them again in Alcatraz. “We became these really good penpals. And I started to ask him about what life was like in Alcatraz with John and Clarence, and could you tell me anything about my uncles that I wouldn’t have known?

“He shared a lot of things – and then, eventually, he says: ‘I’m going to tell you something I’ve never told anybody.’ And he goes into great detail about his involvement in the escape and how he helped them,” Widner tells The Independent.

Bulger had first met the Anglins in prison in Atlanta in 1958, Widner writes with co-author Mike Lynch in their new book Alcatraz: The Last Escape. The brothers, who grew up poor in Florida and showed an early aptitude for petty crime – much to their parents’ chagrin – had ended up behind bars yet again after being sentenced for an Alabama bank robbery pulled off with a third sibling, Alfred.

John and Clarence Anglin were transferred separately to Alcatraz, where they began plotting their escape with fellow inmates Frank Morris and Allen West. Furtively hoarding materials, they began implementing a multi-pronged plan: digging out behind the grates in their cells with spoons and other implements to tunnel to freedom, hiding their progress with touched-up pant and fake replacement grates; creating dummy heads for their beds to fool guards on the night of the escape; and fashioning life preservers and a raft from raincoats gathered from other inmates.

The men planned to hitch the raft to a prison transport boat, then get picked up in the freezing San Francisco Bay by a waiting vessel arranged by another underworld contact, Mickey Cohen, who’d been released from Alcatraz months before the planned escape.

Bulger was advising throughout, he told Widner in his letters, offering expertise he’d picked up from his unexpected hobby of scuba diving.

“He showed them how to make wetsuits,” Widner tells The Independent. “What’s so crazy is that all of what he told me backs up what was in the FBI files; they didn’t take any of their clothes with them out of their cells … they took rubber cement and they painted the inside of the legs of trousers that they were keeping up on top, along with their shirt, and then they tied off their ankles with a black cloth tag, which they found inside of John’s cell.

“They were painted black so they couldn’t hardly be seen, and it also prevented the water from flowing in and out of their clothes very fast, so it kept them warmer longer – and then, of course, he taught them about how to survive if they ever go into the current. He shared a lot of what a scuba diver would do.”

In the end, only the Anglins and Morris would make a break for it; West couldn’t widen the hole in his cell enough on the night of June 11, 1962, as his co-conspirators desperately tried to help but eventually were forced to abandon the effort. West could reportedly be heard sobbing in his cell afterwards.

The others, however, made it out of the complex and to the water, though Morris badly cut his leg and was bleeding into the raft as they attached it with an electrical cord to the intended boat – surreptitiously hitching a ride into the dark waters, where they were then plucked from the water by a waiting white boat, according to the book.

That boat piloted them to land, where the trio were met by a friend and one of the Anglin sisters before scurrying to a small airport, where their childhood buddy, Fred Brizzi, sat behind the controls of a small plane. They took off for Mexico, where they spent some time before relocating to Brazil, where they’d likely be safer and less threatened by discovery.

Bulger took quite a bit of credit for that coup, too.

“The biggest piece of information he gave them, he told them: ‘When you get out, go to Brazil, marry a local woman, have children, and they can never bring you back,’” Widner tells The Independent.

And that’s exactly what his uncles did, he insists – including in the book firsthand accounts from at least one relative and one friend who claimed they visited the pair .

Brizzi, who knew the family from back in Florida, paid a visit to the Anglins in 1992 with a trove of photos and stories – even acquiescing to being recorded as he shared how he’d not only flown the brothers to safety but also visited them at their eventual home in South America.

Widner’s other uncle, Robert – affectionately known among the family as Uncle Man – had also been peculiarly coy in the decades after his brothers’ escape. According to the book, he’d visited them in Mexico and reported on their life there to still-imprisoned Alfred back in Georgia – sparking a notable change in the mood of that brother, who sadly later died behind bars under mysterious circumstances.

Robert was the only member of the Anglin family repeatedly polygraphed, and authorities clearly believed he knew more than he was letting on – rightly, it turned out, given the 2009 deathbed statements he gave to family.

“The final confirmation came from Man himself in 2009 shortly before he died,” Widner writes in the new book. “He shared these words with my mom and sister: ‘Your brothers are fine and I have been in constant touch with them for over twenty-five years.’”

Widner didn’t find out about his uncle’s admission until the 50th anniversary of the escape in 2012, though there had been indications for years within the family – who’d felt “hounded” by authorities – that the brothers had gotten free and clear. Christmas cards, annual presents of roses for the men’s mother and even a pair of mysterious, veiled, “large” stranger women attending her funeral certainly pointed towards their survival.

So would Widner’s deep-dive into public and family records, which turned up even more supporting evidence of the Anglin escapees’ thriving life elsewhere. The escapees’ nephew credits his career as an IT specialist with Georgia Pacific with making him “really good at data analyzing and just seeing the bigger picture, digging into details.”

The book includes details of a deathbed confession from a man who claimed to have been on the boat that picked them up on the night of the escape; it also details how searchers found a raft filled with blood on an island near Alcatraz – blood that likely came from Morris’ gushing leg.

Most compellingly, of course, is a picture Widner took special notice of among the photos Brizzi left with the family – a photo of two men posing in Brazil who, though ageing, look remarkably like John and Clarence. The childhood friend, incredibly, never flagged the photo to family or identified the men pictured as the Anglins; Widner was aghast when he re-discovered it and made the connection while doing research. So was everyone he showed it to; unrelated facial recognition experts have insisted the image does, in fact, show the two jailbreakers.

“Once we find their families, they’re going to have photos with either their granddad or their dad – and I think we’ll get some more information,” he says.

He’s cagey about how far that search has gotten – but confirms “we have somewhere down there that is a specialist in tracking people down.”

He doesn’t say what will happen when they find the long-lost family; he’s certainly hoping for perhaps a reunion and/or more details about his uncles’ lives.

“There is a small, small, slim chance that John is still alive …. I doubt both of them, for sure, but it’s a possibility.

“I love the fact that we’re keeping the story alive,” he says. “It’s been a mission.”

It might sound romantic to believe his uncles escaped the impenetrable Rock, evaded authorities for decades a forged a fantasy life in South America; Widner, however, points not only to family whispers and admissions but also to the trove of clues he’s outlined – and an absence of proof to the contrary.

No bodies have ever turned up; while floating debris surfaced in the immediate aftermath of the escape, Widner writes in the new book, was all part of the plan. The trio felt the detritus would throw searchers off the scent, supporting a conclusion that they drowned … and that’s exactly what transpired.

While the FBI closed its file in 1979, the case remains open for the US Marshals, who continue to search for fugitives until they’re captured or dead.

“I’ve had people who have told me they don’t believe any of this and I always ask them the same question, just like I ask the US Marshals: What piece of evidence have you ever seen that supports your theory?” Widner says. “There is none – so it’s just a theory.

“And I’ve challenged the US Marshals many times: You bring all of your circumstantial evidence, I’ll bring all of mine, let’s get before a group of people [and] see who has the best story.”