City council vote could enable a new Tampa Bay Rays ballpark — and the old site’s transformation

A key city council vote Thursday on a major redevelopment project in St. Petersburg could pave the way to give baseball’s Tampa Bay Rays a new ballpark, which would guarantee the team stays for at least 30 years.

The $6.5 billion project, supporters say, would transform an 86-acre (34-hectare) tract in the city’s downtown, with plans in the coming years for a Black history museum, affordable housing, a hotel, green space, entertainment venues and office and retail space. There’s the promise of thousands of jobs as well.

The site, where the Rays’ domed Tropicana Field and its expansive parking lots now sit, was once a thriving Black community driven out by construction of the ballpark and an interstate highway. A priority for St. Petersburg Mayor Ken Welch is to right some of those past wrongs in what is known as the Historic Gas Plant District.

“The city’s never done anything of this scope,” said Welch, the city’s first Black mayor with family ties to the old neighborhood. “It’s a momentous day for our city and county.”

The linchpin of the project is the planned $1.3 billion ballpark with 30,000 seats, scheduled to open for the 2028 season. That would cap years of uncertainty about the Rays’ future, including possible moves across the bay to Tampa, or to Nashville, Tennessee, or even to split home games between St. Petersburg and Montreal, an idea MLB rejected.

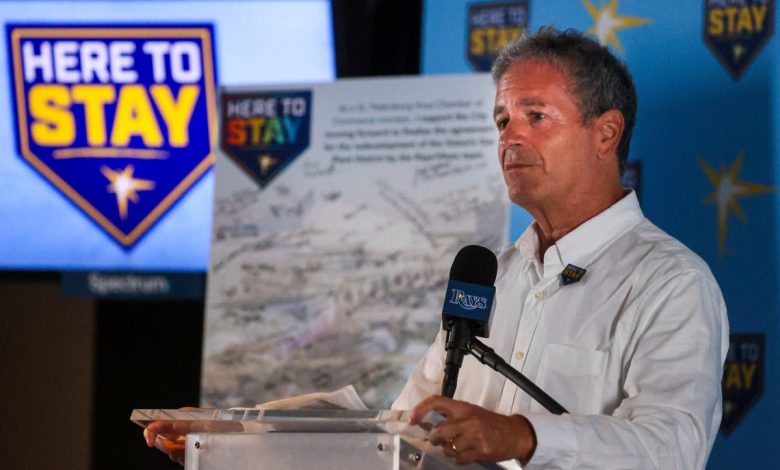

Stu Sternberg, the Rays’ principal owner, said approval of the project — which also requires a vote by the Pinellas County Commission — will settle the question of the team’s future location.

“We want to be here. We want to be here to stay,” Sternberg said Wednesday.

The Rays typically draw among the lowest attendance in MLB, even though the team has made the playoffs five years in a row. This year, at this week’s All-Star break, the Rays have a 48-48 record, placing them fourth in the American League East division.

The financing plan calls for the city to spend about $417.5 million, including $287.5 million for the ballpark itself and $130 million in infrastructure for the larger redevelopment project that would include such things as sewage, traffic signals and roads. The city envisions no new or increased taxes.

Pinellas County, meanwhile, would spend about $312.5 million for its share of the ballpark costs. Officials say the county money will come from a bed tax largely funded by visitors that can be spent only on tourist-related and economic development expenses. The county commission is tentatively set to vote on the plan July 30.

The rest of the project would mainly be funded by the Rays and the Houston-based Hines development company.

The ballpark plan is part of a wave of construction or renovation projects at sports venues across the country, including the Milwaukee Brewers, Buffalo Bills, Tennessee Titans and the Oakland Athletics, who are planning to relocate to Las Vegas. Like the Rays proposal, all of the projects come with millions of dollars in public funding that usually draws opposition.

Although the city’s business and political leadership is mostly behind the deal, there are detractors. Council member Richie Floyd said there are many more ways the ballpark money could be spent to meet numerous community needs.

“It still represents one of the largest stadium subsidies in MLB history. That’s the core of my concern,” Floyd said.

A citizen group called “No Home Run” and other organizations oppose the deal, with the conservative/libertarian Americans for Prosperity contending the track record for other publicly financed sports stadiums is not encouraging.

“The economic benefits promised by proponents of publicly funded sports stadiums fail to materialize time and time again,” said Skylar Zander, the group’s state director. “Studies have consistently shown that the return on investment for such projects is questionable at best, with most of the economic gains flowing to private interests rather than the general public.”

Still, the project seems to have momentum on its side. For former residents and descendants of the Gas Plant District neighborhood, it can’t come soon enough.

“All over this country our history is erased. That will not happen here,” said Gwendolyn Reese, president of the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg. “Our voices will be heard. And not just heard, but valued.”